All Faculty Excerpts

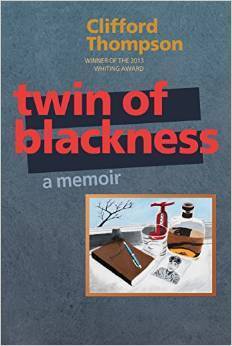

Twin of Blackness

Gotham teacher Clifford Thompson has just seen the release of his memoir Twin of Blackness.

Gotham teacher Clifford Thompson has just seen the release of his memoir Twin of Blackness.It’s a coming-of-age story, but told through the lens of jazz, art, and the ever-changing American identity. National Book Award winner Charles Johnson calls the book “a culturally important memoir that traces an artist’s evolution in the post–civil rights era, a literary odyssey that comes triumphantly to rest in a humanity that transcends small-spirited notions about race.”

Here’s a sampling from Chapter One:

***

My Uncle Brock was missing his front teeth and quite a few others besides. I don’t know if his drinking caused that—he seemed to drink more than he ate—but it couldn’t have helped, just as it didn’t add any pounds to his very lean frame. Because he was so lean, he seemed long to me: long limbs, long, medium-brown fingers that often held cigarettes, long, skinny feet in brown loafers and white socks, a long, narrow face. It was a kind face, with a salt-and-pepper moustache and squinty eyes.

The eyes looked down on me one night when I was about ten, as he sat on the side of my small bed. Other relatives who lived nearby were downstairs with my parents, playing cards, drinking, smoking, laughing. Uncle Brock had heard I was sick and had come to my little room to keep me company, smiling as he talked about girls and this and that in his gentle, whiskey-roughened voice.

Seventeen years or so later, the memory of that voice brought tears to my eyes; it was 1990, I was two hundred miles from that little room and soon to be much farther, and I had just been told about his death.

Usually when I heard Uncle Brock’s voice it alternated with the smoother tones of his buddy and brother-in-law, my father. At our dining-room table they would talk about people they knew, or TV shows, or the most recent NASA mission, or movies they wanted to see but—as far as I could tell—never got around to, or the horses. It was Uncle Brock who later went to Laurel racetrack, the scene of my father’s death the day before, with the ticket that had been found in my father’s wallet. Not untypically, it brought no money.

There is a pairing of voices that reminds me of my father and Uncle Brock’s: the sounds of Coleman Hawkins, the original jazz tenor saxophonist, and Roy Eldridge, a luminary of the trumpet. The obvious relish with which they played together, their humor and pizzazz and down-homeness as they traded fours, make me think of those long-ago conversations between my father and uncle. In my mind, Hawkins—who loomed somewhat larger on the sax than Eldridge did on trumpet—is my father, who had the larger place in my life. Hawkins’s mighty tone and pronounced vibrato could make the air seem to tremble, an effect my father’s voice could sometimes have, more than he knew, on my insides.

In my mind, it is a short step from thinking of Hawkins and Eldridge to thinking of my father and uncle. In my life, I made the journey the long way around, arriving just in time to save my sanity.

Reprinted with permission from Autumn House Press.